Local History

He Put Crystal Lake on the Map – Literally!

John Brink was born in Phelps, Ontario County, N.Y. on January 12, 1811. In his early life John Brink received a very limited education. At the age of 19 he had the opportunity to attend the academy at Lyons, Wayne County, N.Y. John Brink was a natural mathematician and made rapid progress, completing his study of surveying at Lyons.

John Brink was born in Phelps, Ontario County, N.Y. on January 12, 1811. In his early life John Brink received a very limited education. At the age of 19 he had the opportunity to attend the academy at Lyons, Wayne County, N.Y. John Brink was a natural mathematician and made rapid progress, completing his study of surveying at Lyons.

In 1831, John Brink joined the staff of John Mullett, United States Deputy Surveyor. The surveying party headed for Galena, passing through Chicago, which at that time was a government fort. The only residents in Chicago were John H. Kinzie, the Indian agent, George W. Dole (uncle to Crystal Lake’s Charles S. Dole), Sutler for the United States Army, and Mark Beaubien, an Indian trader. Officers and soldiers were also stationed to protect the fort. While in Galena, the surveying party helped to run many of the township dividing lines. While surveying these outlying areas, John Brink and his crew were threatened by the outbreak of the nearby Blackhawk War.

In later years, John Brink assisted in surveying much of Northern Illinois, Southern Wisconsin and Eastern Iowa. He is credited with being the first white man to look upon Lake Geneva (Wisconsin) and gave it the name which it now bears.

On March 5, 1840, John Brink married Catharine A. Throop, a native of Vermont. The couple moved to McHenry County 1841. John Brink was elected McHenry County Surveyor in 1843. He held that post for nearly forty years.

With the coming of the railroad, the Village of Nunda came into existence in the spring of 1855. Nunda was located just north of the Village of Crystal Lake. John Brink established a plat of survey for the Village of Nunda in 1868. Roughly, the borders of the original Village of Nunda included the area which we now refer to as “Downtown Crystal Lake.” Nunda was approximately bounded by Route 176 on the north, Crystal Lake Avenue on the south, Main Street on the east, and Walkup Avenue on the west.

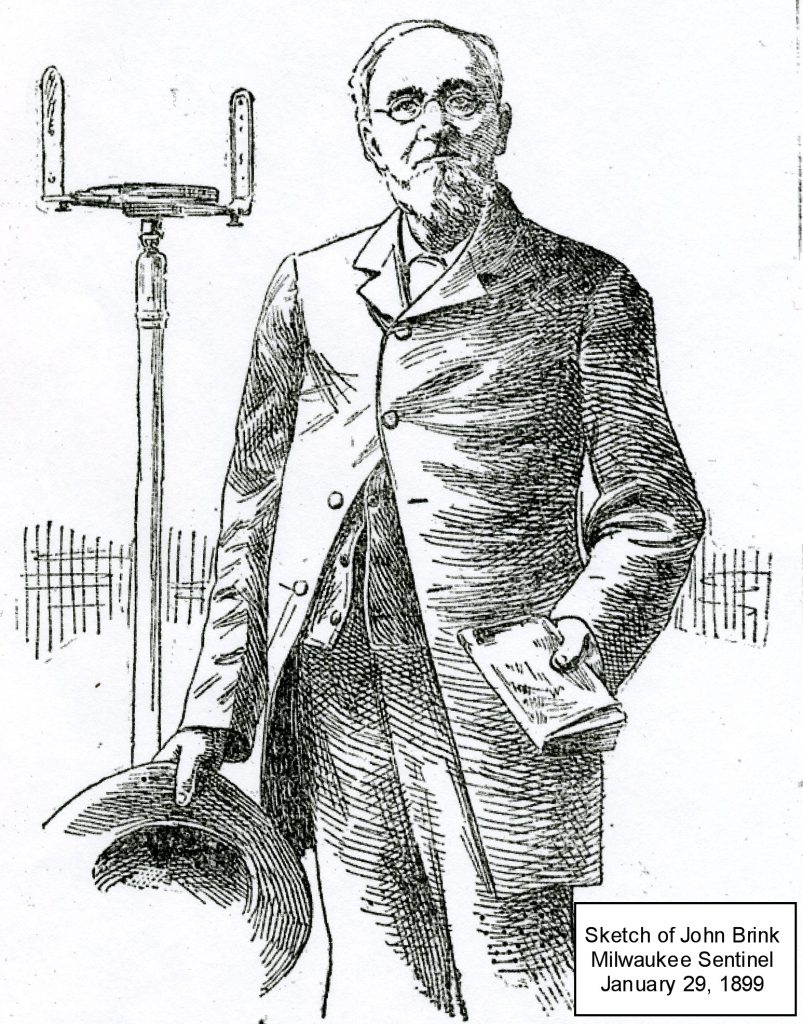

In his later years, John Brink was known to share his great collection of anecdotes and reminiscences of his early surveying days. In 1899, the Milwaukee Sentinel interviewed John Brink. The interview includes comments about Abraham Lincoln, Indian Wars, French traders, pioneer hardships, and more. A transcription of the original interview, as found in the Milwaukee Sentinel, is available at the end of this article.

John Brink died at his home in Crystal Lake on Wednesday, March 23, 1904. He was 93 years old. John and Catharine Brink are buried in the Lake Avenue Cemetery. According to his obituary, “Uncle” John Brink was known far and wide and was loved wherever known.

The Milwaukee Sentinel | January 29, 1899

John Brink, An Old Government Surveyor

“You want to know about some of my early experience as a government surveyor in Wisconsin?” The speaker was John Brink, the old government surveyor, now 88 years old and a resident of Illinois.

“Well, I began surveying before Abraham Lincoln did, although Lincoln was two years older than I. He was born Feb. 12, 1809 and I was born Jan. 12, 1811.

“I began to make government surveys in 1831 under the surveyor general, and Lincoln began as a deputy county surveyor under John Calhoun, of Sangamon County, Illinois, in 1833. It is the only instance in my life where I outranked Old Abe.

“He was a captain in the Black Hawk war, while in the same territory I was running township lines six miles east and six miles south of Blue Mounds, Wis. And I would have run into an ambush of Black Hawks had not Henry Gratiot, government land agent, sent his interpreter to warn us the same day on which Force was killed and Green wounded. We immediately packed our camp and made for Galena, Ill. as fast as we could, where we remained until the excitement of the Black Hawk war had abated. In the fall we returned to our work of running the township lines of Wisconsin.

“From 1831 to 1836 I worked with John Mullet, another United States deputy surveyor for the Cincinnati, O., Land office under Surveyor General M.T. Williams. Up to 1836 we had run the township lines over that part of Wisconsin from where Sugar River crosses the state line, north to the Wisconsin River, thence up the Wisconsin River to Fort Winnebago (now Portage); thence to Fox River and down that river to Green Bay, and thence to the point of the peninsula between Green Bay and Lake Michigan.

Lake Geneva and Its Name

“I first saw Lake Geneva in 1833. Our party had come down across from Fort Winnebago to the state line to establish the first correction line of our survey. We struck the head of the lake at what is now Fontana. Previous to this I had seen many of the lakes of Wisconsin, but nothing to compare with this one in beauty. Chief Big Foot and his Indians were still there, but camped further down the lake. We camped at the big spring which boils out of the bluffs about a half mile above the head of the lake which now feeds the Douglas millponds. Not many rods from the spring, suspended in a tall oak tree, was the body of Big Foot’s son, a lad about 14 years old. They had taken a section of a tree and split it, and hollowed out each half, enclosed the body within, and bound the parts together with withes and sinews then suspended it high up in the tree, safe from vultures and wolves—a romantic resting place in a lovely spot, overlooking one of the most beautiful lakes in the world.

“In 1835 I was running township lines in southern Wisconsin and ran a line through the lake. Our instructions were to plat all lakes, rivers and streams, and preserve all the Indian names to the same. The Indians called the lake “Big Foot” and whether the name originated with the lake or with the old Winnebago chief, of that name, I do not positively know. I am inclined to think, however, the name originated form the shape of the lake. Before the lake was dammed at the outlet its surface was about six feet lower, and its general outline was the shape of a human leg and foot. The upper end of the lake, what is now, Williams Bay, forming the knee cap, and Geneva village, the toe. At that time very little water extended into Williams Bay, and it was only a strong curve to the shore of the lake.

“Juneau, the French trader who founded Milwaukee, and who, by the way, was a personal friend of mine, said we were the first white men to see the lake. Though Juneau had seen it, he said in a jocose way he did not consider a Frenchman a white man.

“In due time I made my returns to the surveyor general’s office at Cincinnati, and the chief clerk put them in his own private desk. When I made my appearance he called me into his private office, and, taking from his desk the plat I had made of Big Foot Lake, and pointing to the name ‘Geneva’ asked:

“’Is that what the Indians call that lake?’

“’No.’

“’Well, what were your instructions with regard to preserving original names?’

“’I was to carefully preserve them.’

“’What do the Indians call it?’

“’Big Foot.’

“’What right had you to change the name?’

“’None whatever.’

“’Then why did you do so?’

“’Because it was too beautiful a sheet of water to be called such an ugly name.’ I then launched out in an enthusiastic description of its beauties and painted the finest word picture I was capable of.

“’But why did you name it Geneva?’

“’Because I was born eight miles north of Geneva at the foot of Seneca Lake, New York, and I thought it a beautiful and appropriate name for that lovely sheet of water in those Wisconsin woods.’

“’Well, Brink, I was raised near there, too, and we’ll let it go on the records as Lake Geneva.’

“In 1833 I made the first government survey west of the upper Mississippi River and stuck the first government stakes in the great Northwest by surveying and staking out forty acres for the village of Dubuque, Ia. No Spanish, no French or Indian land title was good with this government unless claimed prior to 1818. In 1833 heirs and creditors of the old Frenchman Dubuque were trying to get a title to a tract of land ceded in an early day by the Indians to Dubuque. The grant called for twenty-one miles up and down the river and fifteen miles back, including what is now Dubuque, Ia. I was sent by the surveyor general to locate the boundaries of Dubuque’s grant.

“I got an old Frenchman about 70 years old, who was raised by Dubuque from the time he was 5 years old, to show me the corners. Those inland were marked by big piles of stones, while those at the river were designated by large trees, among whose roots were morticed big chunks of lead. After making the survey and comparing my figures with the grant I found the original survey a correct one. The original survey was made by Frenchmen from St. Louis, Mo. At the time I re-surveyed the grant Dubuque’s bones were lying in state in a small stone house about three miles below the survey of Dubuque’s village, at the mouth of Catfish River.

Chicago and Galena in 1831

“The first surveying I did was with Mullet in 1831 when we run the fourth principal meridian, commencing at the mouth of Fever River on the Mississippi River and running through Galena, Ill., to the Wisconsin state line. At that time Galena was quite a city of perhaps 1500 inhabitants. Its principal industry was the lead mines. It was away ahead of Chicago in importance and population. I first saw Chicago in December, 1831. It consisted of Mark Beaubien, John H. Kinzie, Indian agent, and George W. Dole, sutler, and about 300 officers and men at old Fort Dearborn. The whole town at that time could now be stored away in some small corner of any of the Chicago’s present big buildings and the room would hardly be missed.

“In 1838 I went to Michigan and surveyed a strip 150 miles long and twenty-four miles wide into townships. In that tract I surveyed a reservation of 70,000 acres for the Ottawa Indians.

“During the seven years in which I surveyed for the government we frequently came in contact with marauding bands of Indians, but they gave us no trouble, unless I except one occasion, and then the trouble was of short duration. On arriving at camp one evening after surveying all day we found a band of about a dozen Indians squatted on their haunches at one side of the cook’s fire awaiting our return. The chief buck objected to our being in that territory and made himself quite obnoxious by entering our tent (which faced the fire with the flaps turned back), and squatting down in the center of it, as much as to say ‘Here I stay till you get out of my territory.’ We had in our party a dare devil of a fellow who was one of the finest physical specimens of humanity I ever saw. His fingers, all the time we were ‘palavering’ with the buck, had been itching to get hold of him. When he so impudently entered and took possession of our tent, I gave our ‘Hercules’ the wink to pitch him out, which he did by catching Mr. Indian by the seat of his breechcloth and the nape of the neck and throwing him bodily clear over the fire among the other bucks, who all turned and fled with their vanquished chief from the jeers and taunts of our amused but frightened party. They were all young bucks, evidently seeking an adventure, which luckily for our little party our young ‘Hercules’ could give them.

Hardships of the Pioneers

“Our surveying party had two chainmen, an axeman, a cook, a packman, and myself. We seldom camped more than two nights in one place. Our camp equipment was reduced to the barest necessities and we were not supplied with guns to defend ourselves from either wild beasts or Indians. Our expeditions would last from five to eleven months. Sometimes we had to build a cache for our supplies. They were usually made of big logs built up enclosing a hollow square, proof against both large and small animals. We had three pack horses, and our packman was kept busy moving our camp and packing our supplies from the cache to the camp. One had to be an experienced woodman to be able to do this work.

“Every other day after our work was done we would have to locate the new camp the packman and cook had made. I think I know something of the hardships of pioneer life, for I have waded through miles of swamp and on more than one occasion have had to swim streams when the ice was running.

“I think I do not exaggerate when I say I have been three months at a time without having all my clothes dry on me at one time. When we get into camp at night we are ready to eat our supper and lay down and sleep. No time to set around a campfire and dry wet clothes, and it made too much luggage to carry extra suits. You may rest assured we had no fancy smoking gowns, pajamas, or night shirts. And we did not see much of fashionable society, though we did attend one celebrated wedding, but were not given an opportunity to kiss the bride.

An Indian Chief’s Wedding

“Ku-acus-kum, the old chief of the Ottawas, must have been over 60 years old when he married a young squaw, although he had an old one about his own age, who did not look as though she enjoyed the wedding ceremonies, for she sat alone outside of the circle which enclosed the bride and groom. There were about 150 of the chief’s followers present and the wedding was celebrated at the mouth of the Manistee River. We were camped on the opposite bank and when we arrived a circle of about one half of the Indians present had been formed around the chief and his young bride. One of the bucks, probably the Medicine man, went through some kind of a pow-wow and ceremony, while those in the circle danced around to their yells of ‘Ki-yi,’ ‘Hi-yi’. They had no musical instruments of any kind, not even a drum or gourd. The old chief made us welcome, but some of the young bucks had fire water and were getting pretty hilarious. One of our men could understand their jargon and he heard mutterings because we were there. We concluded we would be safer across the river in our own camp. So we gave the old chief and his dusky young bride a wave of the hand as a parting salute and withdrew without kissing the bride or partaking of the wedding feast. That was the first and only time I entered society while I was surveying for Uncle Sam.

How We Celebrated July 4, 1838

“On July 3, 1838, while going through some heavy timber in advance of my men I heard something fall to the ground from a tall hemlock tree. I thought by the sound it was a rotten limb, but on closer inspection found it was an old she bear with a cub. She was traveling in a circle around the tree and around the cub. I had heard if an animal fell on its head it would daze it so it would travel around in a circle. I supposed the crash I heard was the bear falling from the tree. I thought I would get near enough to her to strike her over the head with my compass staff and add to her confusion, but when I saw the cub thought I had better make sure just how badly stunned she was. So I raised my staff over my head and gave as big a yell as I could. The cub went up the tree like a squirrel and the old bear raised straight up on her hind legs and showed all her ivories. I don’t know which was more frightened, but I guess I was, while she was most surprised. We faced each other till the cub got at least 50 feet up the tree, when I mustered up courage and shook my staff and yelled again. At that she dropped on all fours and came straight for me, and I turned and ran, and if ever a fellow came near flying it was I. Fear reduced my weight and increased my strength, and I was soon back with the boys. When the bear found herself confronted by four yelling men she turned and disappeared into the forest. We went back to the tree where the cub was and discovered another cub in another tree. We felled the trees and killed the cubs and celebrated the glorious fourth by remaining in camp and feasting on bear meat.

“Talking with old chief Ku-a-cus-kum afterward about my adventure he told me I should never run from bear, as they would always raise their hind feet if you faced them. Keep a good knife in your hand, keep your arms high, and when the bear takes you in his paws reach over and stick your knife between his ribs. The old chief bared his breast and allowed me an ugly scar several inches long where a bear had bit him before he could kill it with his knife. He said when the old bear turned to run from us she was too badly frightened to return to her cubs.”

John Brink is still living at Crystal Lake, Ill., a hale, hearty old gentleman of 88 years. “Uncle John,” as he is familiarly known to a large circle of friends and acquaintances, was until the last few years frequently employed to survey farms, villages, lots, etc. Having in his life time seen a wilderness changed to fertile, thickly populated and wealthy district, he is full of interesting reminiscences.

Learn more about Brink Street.